Samurai Spirit - Taking a Chance on Some Samurai Guys

Published by Funforge - 2014

Designer: Antoine Bauza

Head Artist: Victor Corbella

1 - 7 players ~ 45 - 75 minutes

Review written by Luke Muench

Years ago, Samurai Spirit was one of the first games that I considered getting rid of back in my early days of board gaming. The game felt simple, slow, and ended with us losing without us knowing what we could have done way more often than we liked. It was a frustrating, obnoxious, colorful, mess of an experience.

After some thorough contemplation, I decided to go back into this war between our brave, perilous samurai and the waves and waves of villainous ninja to see just what made this game tick. And what I found… was blackjack.

Having been a blackjack dealer for a time, there was a certain… nostalgia to the game, so I decided to keep it, eventually considering it one of the greatest co-ops of all time, but the wind’s favor is fickle, and now it’s time to take another critical eye to Samurai Spirit.

Fighting For Your Life

Know your enemy and know yourself and you can fight a hundred battles without disaster. - Sun Tzu

Samurai Spirit, like most co-op games, tasks players with trying really REALLY hard not to die. Which, of course, like most good co-op games, you will die. A lot. Like, 6 out of 7 times. It’s so brutal that when you pry open the box, the familiar lid-squeak starts to sound more like a taunt - “Really? You’re gonna try THIS again? HAH! Good luck with that.”

The Samurai win the game if all players are able to survive 3 waves of ninjas while also keeping one building intact and one villager alive; that’s a lot of stuff to protect. Like a leaning tower of porcelain vases held together by some twine; eventually, one of them is gonna get smashed, and more will spitefully crash to the ground in the process.

This means every action is vital and must be carried out with precision. Players are forced to collectively manage what few resources they have in hopes of lasting long enough to make it through the hour run-time.

Turns are very simple; on your turn, you will do one of three things:

Draw a ninja card to deal with.

Pass your power token to another player.

Pass

This easy, quick framework leads a lot of players to initially take this game for granted, and if you don't have someone to explain the subtle nuances of this game, you’ll likely find yourself questioning why your friend would hate you so much to make you play such a mindless title.

You will most often (by far) draw cards, each adorned with a few symbols to be mindful of:

The number at the top left of the card (commonly 1 through 4) shows that ninja’s strength and how much strain it puts on you if you fight it.

The symbol in the bottom left corner of the card illustrates a punishment for fighting this card, assuming it’s at the top of your pile of baddies.

The symbol at the top right of the card shows which resource this ninja is attacking, allowing you to defend that resource if you so choose.

If there’s fire in the background of the card, that can be bad, but only if this ninja finds itself in the spy pile (which we’ll get to later).

All this information comes together and asks you one question; do you fight this card or defend against it?

Fighting a card adds its value to your combat track; if you combine card values to hit the highest number on your board, you unleash an extra special ability specific to your character and replenish your combat track partially, helping you fight more baddies. Go over this value, though, and you’re forced out of the round, burning down one of your precious fences in the process, allowing the fire to reach ever closer towards your houses.

Defending a resource means that card doesn’t do anything negative to you and you protect that thing from being damaged by your negligence at the end of the round. Each resource can only be protected once each round by each player, meaning that once that slot is filled, you’ll be forced to fight other, potentially worse minions down the road. Plus, if you don’t defend a resource before the end of the round, the team loses one of that resource, making you in part the source of the bad things happening. Nice going, samur-die.

Which cards you interact with each turn of the game will have huge repercussions later on. Fighting a minion early on that does fire damage to the town and choosing not to cover it could force you to burn through your resources quickly. If the first minion you fight in the round is value at “1”, you’ll be incredibly limited in what you can fight after you partially refresh your combat track.

Luck Be A Ninja Tonight

If I should come out of this war alive, I will have more luck than brains. - Manfred Von Richthofen

This is about when you start to wonder “what is the distribution of cards in the deck?”, a question that has an ever changing answer. Samurai Spirit comes with 52 cards with an even number of 1’s, 2’s, 3’s, and 4’s to fill that roster, but only 7 cards are added to the deck per player, meaning there are always at least 3 cards removed from the deck. This results in the first round having a new, deeper meaning as players scope out how many of each card are in the deck, what symbols are more prolific than others, how important it is to defend one thing over another, and so on.

Then, after the 1st round is finished, a 5 value card per player is added to the deck, adding some hulking brutes to scare players, as they can make a serious dent in your fight track. And if you manage to make it to the 3rd round, bosses appear, each 6’s and each with their own brutal and often disastrous negative effects when they are fought.

This also results in players understanding how many turns each player will have roughly; I say “roughly” because card effects and player abilities can alter this in ways that are both positive and negative for the team, mitigating the luck headed in the players’ direction.

Yes, each character has their own crazy special ability that is always active, allowing them to help both themselves and others. On a players turn, they will always be able to use these powers, like being able to pass odd-numbered cards, fighting 2 enemies each round, or killing enemies drawn if their value is the same as what’s already in their fight track. Additionally, rather than drawing a card, you can lend this ability to someone else, helping them better deal with their turn, which can be critical if they’re low on health or need to get rid of a particularly nasty enemy. That said, lending powers does have a price; the top card that would have been drawn is placed in the spy pile.

At the end of the round, there’s a 50% chance that the card in question has flames in the background, meaning that this arsonist ninja burns down one of the town’s fences, or worse, one of the houses if no fences are left. If there’s no fire though, then no harm no foul. This aspect provides the game with a palpable tension as players wonder if they’re willing to risk putting juuuuuuuuuuuuust 1 more ninja into the spy pile if only to squeak by another few turns.

It’s easy to look at this game and see an insurmountable amount of luck gazing out menacingly, but there are a lot of tools at the players disposal to deal with it, as long as everyone is paying attention. Samurai Spirit was the first game that ever made me feel like a part of a team, with each member having their own powers, roles, and insights into the oncoming threat. Many games have been sent quietly pondering and discussing what each person should do on their turn, almost like a council of elders deciding the fate of the village. One misstep and the whole place will burn to the ground, but with just the right touch, maybe we can make it through the night.

And sometimes that means doing absolutely nothing.

To Pass Or Not To Pass

The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his. - George S. Patton

The final action a player can take sounds ineffective and boring; why would a player voluntarily stop playing the game for a few turns until the round is over? Surely there must be another way?

Well, consider this; it’s the start of your turn. Your combat track is at an 8 out of 9 and you’ve defended all 3 of your symbols to the left of your board. Chances are that you’ll draw higher than a 1, busting you out, forcing you to burn a fence and pass anyway. Better to pass now and not suffer an additional consequence, right?

While that was a more extreme and obvious example, there are a few situations where tactically passing can be the difference between life and death for the team, especially if player death is on the line due to negative card effects.

A player’s health is the last and perhaps most intriguing puzzle of them all. At the start of the game, everyone plays as your average, human samurai guys, looking buff and cool to the touch. If they take 1 damage, whatever, they can shrug it off like bros. But if they take a 2nd damage, oooooooooooOOOOOOOOO, now you’ve made them MAD, so mad that they transform into their fursonas, ranging from a tiger with a 6-pack to a dapper-looking fox. This furification isn’t just to look sexy, though, it increases their fight gauge (allowing them to combat more baddies) and improves their kiai, making it more beneficial to hit your high-mark.

However, you cannot heal either of those two damage points you’ve already taken; once you enter this bestial form, there’s no going back. With 2 remaining health points, you have to be extra careful; lose those and it’s game over for everyone. This means that players will, at some point, want to take damage in order to power up and fight off the bigger enemies later, but they’ll have to do so cautious and intelligently in order to not push themselves too hard.

Some Serious Chinks In the Armor

War does not determine who is right, only who is left. - Bertrand Russel

Now, I wish I could leave it at that. I wish I could say, “Wow, I was wrong, this IS one of the best co-ops out there.” I wish I still liked this game as much as I did way back when.

But here’s the thing, the naked, furry truth of the matter; before this review, Samurai Spirit sat on my shelf untouched for months. Every time I looked at it, considered it, I thought to myself, “No, this isn’t the right time for that.” And it wasn’t, because if anything, Samurai Spirit aggressively rewards devotion, but little else.

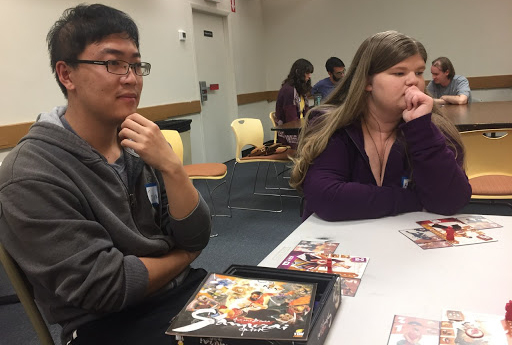

The day after I originally drafted this review, I went to a local gaming MeetUp where I attempted to teach five lightly experienced gamers to this co-op, each drawn to it by the beautiful artwork and fun themes. After the first round of play, though, I suddenly grew tired, even exhausted by the experience, and the players looked to be the same way.

In order to have a chance at winning the game, you need to pick your character layout carefully, but often in obvious ways. If I can pass even-numbered cards, then the character who ignores the negative effects of those cards should probably be adjacent to me. So while randomly dolling out abilities is a recipe for disaster, picking them feels more like an inevitability once one person picks the first character.

Throughout the game, I had to explain the rules 5 or 6 times, reminding me of just how many nuances are present here. Cards and characters are covered in icons, each “simple” action has repercussions 5 turns later for other players, and it can be hard to recall who does what in terms of their abilities.

But more frustrating, I began to feel like a reluctant DM. Samurai Spirit is rife with alpha gaming, to its core. All information is public, and often times the game is best when everyone is working together to devise a plan of action to execute on. That being said, new players will have no idea what a good plan looks like, often looking to me for advice. So either I become forced to make most of the moves of the early game to help teach everyone general strategies or I sit back and allow them to figure the system out for themselves, which is no fun for me and can actively frustrate others when they have no clue what to do. There were many instances when people would just tell others what they “needed to do” on their turn, to such an extent where I needed to speak up about how players “needed” to stop quarterbacking.

The final killing blow was when one player in a seven player game was knocked out early in the 2nd round, busting due to an unlucky draw. This meant that he would have to wait out the rest of the round, roughly 20 turns, before he would be able to do anything else. Since the number of cards scales based on player count, games can vary from half hour to a massive 2 full hours slog. And while the game doesn’t have player elimination, it certainly can lead to instances where you sit around doing nothing for almost a half hour, and that, to me, is an unacceptable mechanic in any game.

Now, some may argue that this game may be better at smaller player counts, maybe 3 or 4, and that may be true, but the game clearly sells itself on being a 7 player game, a count that BGG users suggest is the best way of playing the game. While less players can make the game more manageable, it also makes the game much easier, as well as susceptible to the RNG of what cards are excluded from the deck at the start of the game. You might end up with a deck flooded with 1’s or with very few villager icons, making each experience more and more inclined to some unfortunate odds. And ultimately, that still doesn’t remove the barrier to entry, as players need to play the game 3 or 4 times before becoming familiar enough with the game to be competitive without someone guiding their actions.

A Spirited Experience

The two most powerful warriors are patience and time. - Leo Tolstoy

There was a time when I would freely pronounce to the heavens that Samurai Spirit was by and far my favorite co-op game, adorning my shelf in high esteem, but now I have the sneaking suspicion that it won’t last for much longer.

It forces me to scratch my brain in ways I enjoy, makes me genuinely feel like a part of a team, and forces me to think long and hard before acting, but it asks too much. In order to wring out the best experience from this game, I’d need to draft the same team again and again, players of equal interest, dedication, and skill level.. That leads to an inflexibility that, much like the rigid samurai code, leaves little room for fun.

Who Should Get This Game: Those who don’t mind stumbling through the first few games and plays with the same group week-to-week.

Who Shouldn’t Get This Game: Anyone who is bothered by alpha gaming or doesn’t want to think too hard when playing games.

The Cardboard Herald is funded by the generous support of readers, listeners, and viewers. If you'd like to help support, you can find our Patreon here.