Carcassonne

Designed by Klaus-Jurgen Wrede

Published by Z-Man Games

2-5 Players ~ 30-60 minutes

Review written by Jack Eddy

I am terrible at Carcassonne. Sure, it’s one of those evergreen gateway games that is friendly and approachable for the whole family. I mean, yeah, I know some of the "hot strats"; how to seize the moment-to-moment opportunities to get quick points. But something about drawing tile after tile turn after turn urges risky behavior in me, driving me to press my luck in this not-really-a-press-your-luck game. In the end I think it comes down to the fact that I am a sucker for the mega castle.

Tile Laying 101

There are two main things you need to know to get your Carcassonne on. First - this is a tile laying game where all players are building the expansive, beautiful, and cutthroat French countryside, populated with winding roads, breathtaking castles, and serene monasteries. On your turn, you draw a tile and place a tile which must connect to at least one tile already in play. The catch is that like sides must always match like sides. The open face of your castle can never butt up against a wandering road.

The second thing you need to know is that to score points, you gotta employ your little posse of wooden workers, commonly called “meeples” (speaking of which, the now ubiquitous term meeple was coined by Alison Hansel in reference to these Carcassonne figures). When you place a tile, these duders can be set on a road, castle (actually called cities, but let’s be honest, they are totally castles) or monastery, or laid down in the grass, so long as that feature is not already claimed by another player (ie. the road you are connected to doesn’t already have some dude). Aside from the farmers lying down, whenever a feature is “completed” (castle walls surround the town, roads have two ends, or monasteries have been completely surrounded), your meeple is removed and you score points based on the size of the feature.

But here’s the thing you REALLY need to know about Carcassonne, and the secret sadistic nature hidden just underneath the game’s pastoral pleasantries; in the right hands, this is a game of sabotage and hostile takeovers. If you build a road with your meeple, spending time to carefully curate a nice long stretch of 9 tiles, and I have an unrelated road with my own meeple that I manage to connect, now we both get those points. Thanks! I hardly needed to do a thing! Alternatively, let’s say you are working hard on this beautiful castle, your own little sanctuary in the countryside. I can drop down a tile in there, or even nearby, that makes it nearly impossible to complete; condemning your poor worker to isolated doom.

And speaking of doom and the end of all things; the game ends when a the final tile from the pool is placed, at which time the farmers and incomplete features are scored. Whoever has the most farmers in a field (connected green area), gets 3 points for every castle bordering that field. The thing is that in Carcassonne, there may be several fields due to well distributed infrastructure, relying on roads and castles to divide the landscape -OR- there could be only two or three MEGA fields, and the farmers in control get all the dough. As is true in real life, it is true in Carcassonne; do not underestimate farmers.

I see fields of green

But great gameplay on its own does not imbue cardboard with the longevity and acclaim that Carcassonne has enjoyed. This game has a spectacular table presence, looking more like a puzzle or patchwork quilt than a snappy strategy game, which has undoubtedly played it’s own part in converting new gamers to the hobby. As you’re nearing the end, the minimalist and abstract design is breathtaking, with patterns familiar but wholly unique to each game that you play.

And while this may be the prototypical “dry euro” theme so often vilified in the hobby, I think that’s missing the point. The simplistic, elegant, and most importantly, abstract theme is what makes this game so damn approachable. For those who want die hard competition, the theme is thin enough for you to “see through the matrix”, and begin considering each turn as a number of points and possibilities. On the other hand, less competitive types may enjoy the simple pleasure of watching the peaceful and welcoming landscape develop before their eyes. Either way, the look of the game facilitates the type of experience players want out of it.

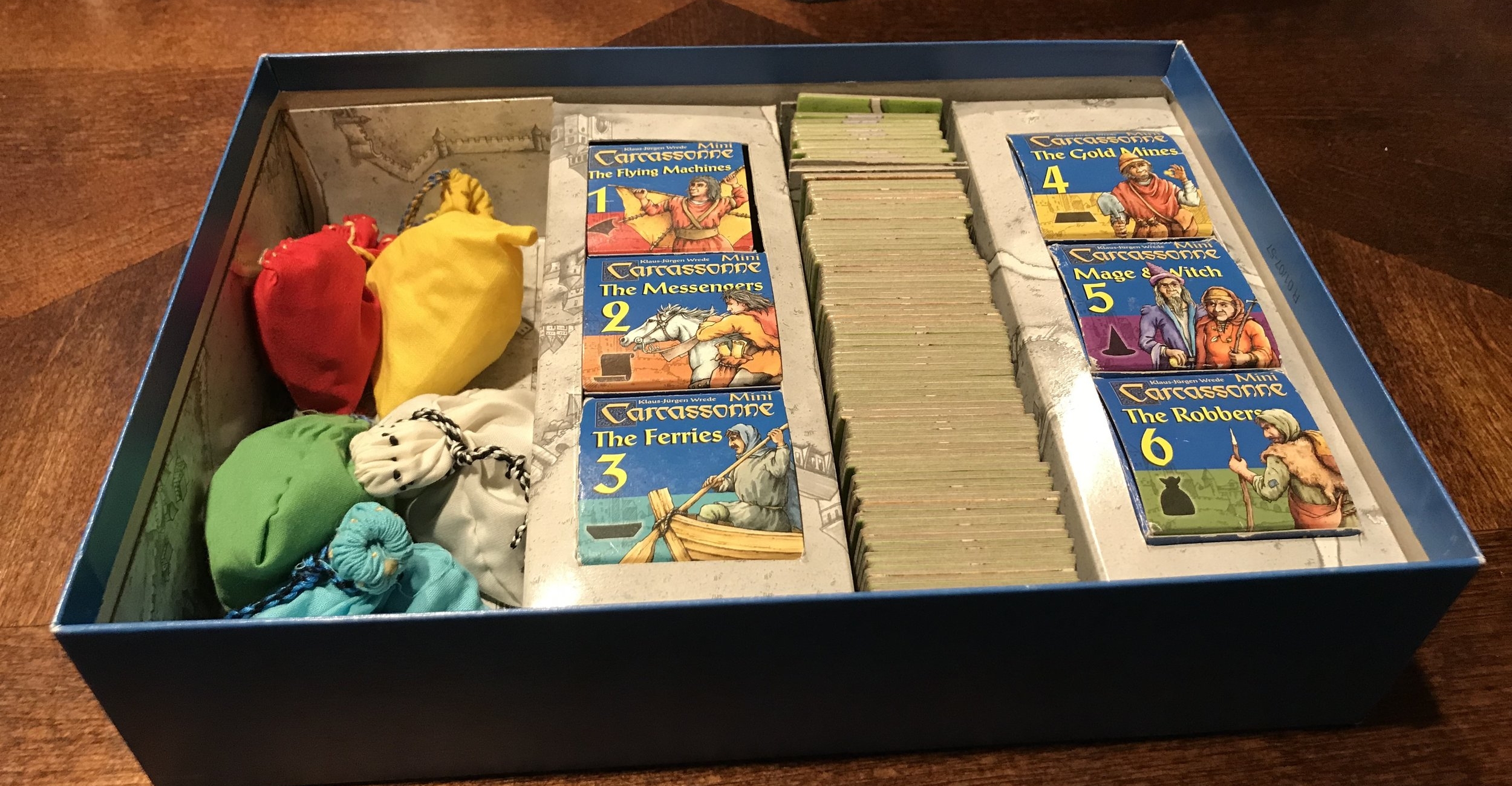

I tend to get crafty with the games I love the most. Here's an early example of some player bags I made and a razorblade's attempt at making a custom insert for the 6 mini expansions.

Why I love the Mega Castle

But here’s where my aforementioned struggle comes in. Sure, not everyone is going to want to play full contact Carcassonne, but the advantages for being cutthroat are tempting. In a game with three complete carebears, one scheming opportunist can really take advantage of everyone else’s hard work. Personally, I fall somewhere in between. I won’t hesitate to connect our two features if it’s convenient, but rarely will I make it an object of strategy. No, I focus on the Mega Castle.

You see, unlike the other features in Carcassonne, castles have a unique property. They score 2 points per tile that comprises your castle and an extra two points for each pennant* housed within the castle, but only if completed during the game. The castles suddenly drop to half their value at final scoring if they remain incomplete, meaning you take great risk and great reward for completing a castle.

And there are few things in this hobby as satisfying, nor as terrifying to witness, as someone completing their 10+ tile mega castle. Rocketing 20-30 points in one shot can be devastating, but it relies on so many things going right; your opponents not finding a way to sneak in, you drawing into the right tiles, there being enough tiles in the game to reasonably accomplish your monumental goal…

But that’s the awesome thing about Carcassonne. It’s so simple and encourages you to take risks because it intends to be a friendly game that wants ALL players to succeed. Heck, my version of the game even has a rule that when you draw your tile, you are to reveal it to all players and as a group discuss where the best possible placement is. Carcassonne is as idealistic and naive as the peaceful and universally prosperous depiction of 18th century French country life; and I really dig that.

No, my castle won’t always succeed, but at least I’ll always get some points. And sure, I’ll claim other features as sensible because I want to win, but Carcassonne is one of the few games in my collection that understands that winning can be a secondary goal to having fun, and the fun of the game is what you make of it. With very limited tools, the game throws me into a sandbox and says “knock yourself out, kid”. So whether I’m looking to risk it for the biscuit with a big point win, or I’m just looking for the tabletop equivalent of doodling, I’m always happy for a game of Carcassonne. After all, I can always find comfort and purpose in my pursuit of the Mega Castle.