Cyclades

Designed by Bruno Cathala & Ludovic Maublanc

Artwork by Miguel Coimbra

Published by Matagot - 2009

2-5 players ~ 60-90 minutes

Review by Luke Muench

There are few genres more polarizing and ambiguous in their definition than what the community has dubbed “Dudes on a Map”. Some have intricate, detailed rulings on movement and attack patterns, using rulers to measure out grand battle plans, full of nitty gritty details. Others are like Risk; long, sometimes tedious ventures that test one’s patience as much as it tests your strategic wiles. It’s not a genre for everyone, and the in-your-face nature of these games aren’t necessarily inviting to those who are unsure of what these games have to offer.

But hark, what’s this? Down from the heavens does Cyclades drift, as if the gods themselves deemed it worthy to be cast in their own image. For truly does Matagot’s first big box mythological extravaganza stand out from the crowd as a wholly unique, invigorating, and inviting package to players of all sorts.

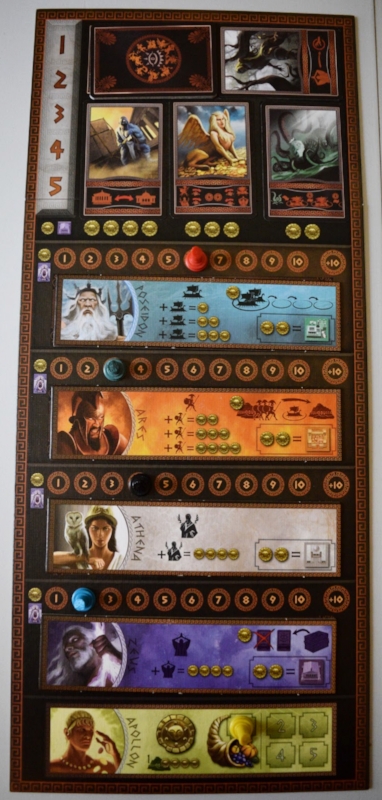

Cyclades is a game that, at first glance, appears like any other “dudes on a map” game. A board dotted with soldier minis of various colors? Check. Dice set aside for combat encounters? You bet. But beside this typical layout is where the game really happens; a rather colorful and elaborate board featuring a mighty pantheon. Zeus, Athena, Poseidon, Ares, and Apollo sit, stoically waiting for players to fight feverishly over them, not with troops, but coin.

At its heart, Cyclades is a bidding game. Each round, players will have a chance to claim one of the gods for themselves, spending their limited pool of coins in attempts to gain their power for the given round. While a seemingly simple task, players who take their turn after yours will have the opportunity to outbid you, forcing you to bid on another god altogether. Timing and planning is a player’s best friend in this vast realm of seas and islands, usually meaning the difference between a victorious military march and the swift and catastrophic destruction of your plans.

This is further compounded by the fact that the order the deities activates in changes round to round at random, meaning that turn order becomes quickly important. While you may desperately need Poseidon’s help, he’s not going to activate until it may be too late. You may want Athena’s help, but she’ll be going first, allowing you to manipulate the board just enough where it might be worth it. This balance of figuring out when to strike and what sacrifices to make only assist in creating an atmosphere of thoughtful strategy.

While each deity provides different abilities and resources, they also allow you to build one of the four structures that combine to form a Metropolis; control two Metropolises at the end of a given turn and you win. This scoring system is simply marvelous in how it can keep all players involved for the duration of the game. Your opponent just built a Metropolis, sure, but there’s no reason why you couldn’t try and march over there next turn and take it for yourself. Or perhaps you’re building a band of Philosophers to erect your own Metropolis in due time. Every single building you build is like a neon sign announcing what’s up for grabs, with the exception that a player’s last island can’t be attacked unless it would win the attacker the game.

Poseidon and Ares largely control the militaristic portions of the game, but do so in a slow, methodical fashion. In order to invade a given island, you must first invoke Poseidon to build and line up your ships in a manner to create a clear path across the ocean from where your troops are to another location. Only then can you, on a future turn, bid on Ares, who allows you to build an army and actually march those troops to their ultimate destination. This makes combat less of a sudden and jarring experience, instead forcing players to telegraph invasion plans well in advance, allowing others to gather defenses in hopes of discouraging such attempts. Players can also have their ships fight, potentially destroying that once convenient pathway to victory.

Zeus and Athena handle the more passive effects, generating priests and philosophers. Priests make it so a player has to pay fewer coins when bidding, making it much easier to outbid your opponents for a fraction of the cost. Philosophers apply steady pressure to your opponents, as they create a Metropolis once you have gathered four. These act as catalysts for tension, pushing each player to be that much greedier as they struggle for supremecy.

At the end of the day, coin is all that matters in Cyclades. It’s what you use to buy the buildings you need to create Metropolises, to afford the abilities of each god, to accrue more troops or ships if need be. Other than some slight bonuses, money is the only way you’ll have any chance of victory. Luckily, Apollo is here to help, providing one player with an extra cornucopia to place on the island of their choice. Cornucopias produce one coin at the start of each turn, rewarding those who have settled on plentiful islands or placed their ships on trade routes. Additionally, players can receive monetary donations from Apollo, depending on the state of the board. Most players will only gain a modest one coin hand-out, but those who only have one island left will get a whopping four coins for their troubles. Because of this, I’ve spent some games barely getting by with a single island in hopes of gathering a sizable treasury for the late-game.

I say barely getting by because each island limits how many buildings you can have on it, meaning that it’s near impossible to build a Metropolis with a single island. On top of all this, each building besides Athena’s will give a player the appropriate passive buff. Ares’ and Poseidon’s structures give a plus one buff to any land or sea battles respectively, as long as they take place on or next to the island on which the building resides. Zeus’, on the other hand, provides discounts for creature cards.

Yes, the mythological beasts of yore make an appearance as well, some as gorgeous and gargantuan minis that stomp about the board, making their presence known. Each round, as long as a player doesn’t bid on Apollo, they may purchase one of the creature cards laid out, gaining an immediate boost, potentially stealing resources from others or flying your troops to a specific location. Creatures can be powerful and devastating allies when used correctly, leading to some of the most exciting and gratifying plays of a given game.

As you might have guessed, there is a fairly varied pool of strategies to pull from, allowing players to attempt different methods and ideas with each playthrough in hopes of discovering all the secrets held within Cyclades’ watery catacombs. That isn’t to say this is a complicated game; the rulebook is about four pages long and new players catch on to the basics quickly. But within this simple format, there is a ton of options and ideas to touch upon, only further supported by a few expansions.

Speaking of which, I’ve seen a lot of reviews and blogs claim that Cyclades isn’t good without the Titans expansion, and while I won’t go into too much detail as to what that pertains, I’d like to address the allegation. Titans, amongst other things, adds a new board to play on, one that, rather than being filled with little islands, is comprised of a couple land masses. This, by and large, is an attempt to make the combat of the game much like any other “dudes on a map” game. Rather than being limited by the sea, combat plays more like a game of Risk than anything else. Poseidon’s role in the game is also greatly diminished, although there are some profitable trade routes to place your ships on. On top of this, a new unit that is introduced, the titans, allows players to fight on any player's turn by spending coins. Again, this works to remove the value of what the base game introduced, making it easier to just fight your way to victory.

In other words, Titans takes away much of the unique identity that the base game fosters, turning it into just any other “dudes on a map” game. While some may claim that this is the only way to play the game, I heartily disagree; in my eyes, the grand strategies and ocean voyages are what give this game such a strong and individual identity.

Now, Cyclades certainly isn’t perfect, with a handful of flaws ultimately holding it back. The first and most prominent of these, in my eyes, is how combat is handled. While the number of troops you have present in a fight does matter, each adding one strength to your attack, each player does roll a single die, adding between zero and three to their total strength. As one might expect, this can lead to your battle strategy falling apart due to crummy luck, but a wise player can account for this and bring enough troops or hedge on the odds. This hasn’t greatly affected any of my recent playthroughs, but this is a very real possibility that might put off some players.

The other primary issue comes from the balancing of the various creatures, as there are some beasts that are clearly superior to the others, namely the pegasus. With the ability to instantly transport any number of troops from one island to another island, the pegasus can be a wildly powerful and game-changing card, one that’s often fought over the moment it appears. Due to this, entire strategies can be shaped or around to stymied by the sudden, opportune appearance of the card. Fortunately, Cyclades allows for some self-balancing through the auction system - if there is a very powerful monster available, players will pay dearly to go first. Still, this card has warranted deep discussion on BoardGameGeek and is worth talking about.

But if those are my only concerns about the game, it’s abundantly clear to me that Cyclades is a clear stand-out within the board gaming hobby, having become my favorite game to date over the last couple of years that I’ve owned it. The unique way it handles the “dudes on a map” system makes it a thought-provoking and brain-burner of a game, yet provides a certain accessibility to anyone who tries their hand at it. The theming and artwork is marvelous, the components generally of high quality, and the design is built in such a way to keep me coming back to it time and time again. It is a wholly immersive and rewarding experience to invest oneself in this world of islands and the warriors that inhabit them, and one that I intend on revisiting for the rest of my board gaming days.

Luke Muench is a regular contributor to The Cardboard Herald and host of the Budget Board Gamer youtube series.

Love Cyclades? Check out The Cardboard Herald's review with co-designer Bruno Cathala on episode 14 of our podcast. You can listen to all of our interviews by finding The Cardboard Herald on iTunes, Stitcher, or www.cardboardherald.com.